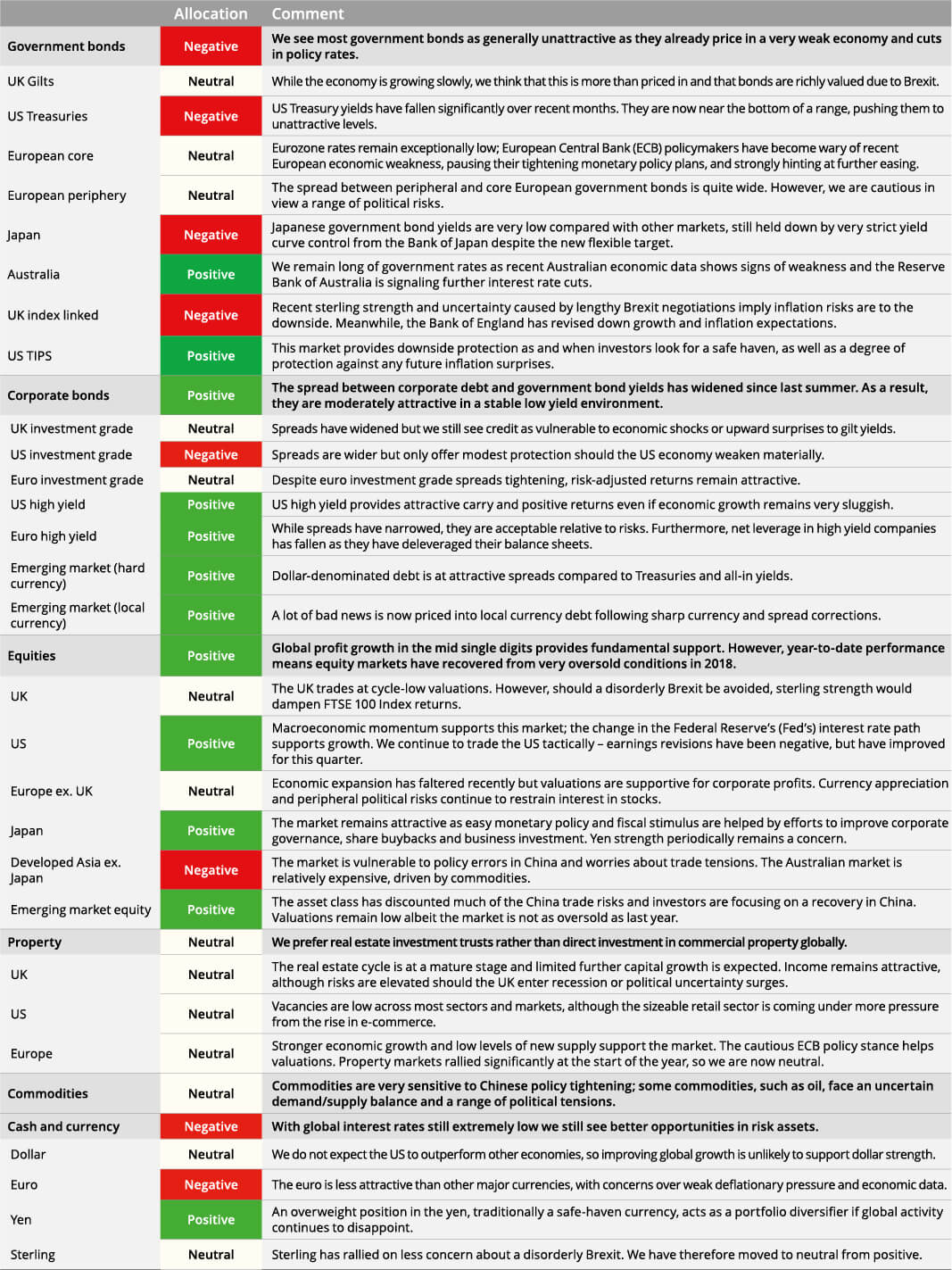

Tactical Asset Allocation (TAA)

The multi-asset team’s view on bonds, equities, commercial property and other assets will affect asset allocation over the coming months. When making these asset-allocation decisions, we first consider the global investment outlook for each asset class (e.g. government bonds), followed by views within that market (e.g. the US versus Europe, or European core economies against peripheral countries). The views of individual asset class teams may differ to this multi-asset view.

TAA Model Allocation - as at July 2019

Foreword by Andrew Milligan, Head of Global Strategy

Our latest quarterly Global Investment Group meeting discussed the backdrop for financial markets during this investment cycle. Looking back over 2019, there have been many positive and negative aspects to consider. On the one hand, equity and bond market returns have been rather strong this year, benefitting from the realisation in the Spring that a global recession was not occurring. On the other hand, there have been growing concerns about a range of political and geopolitical risks, especially related to global trade. These have already affected business and investor confidence, and caused a sea change in monetary policy thinking.

Where next?

Successful investing involves extracting important signals from a blizzard of noise. Newswires may focus on the implications of the latest Trump tweet yet, as several of our articles consider, there are always important structural drivers to include in our analysis. We examine some of these in the Spotlights article, where Frances Hudson, global thematic strategist, considers the long-term drivers of healthcare. The outcomes have important implications for a sizeable part of the equity market, and also feed into the analysis which underpins our strategic asset allocation views.

The Economic Global Investment Outlook

The economic outlook is discussed in detail by our chief economist, Jeremy Lawson. The base case is that the world economy will see limited growth of about 3% a year in 2019 and 2020. However, this requires a further round of policy easing in the major economies, led by a reassessment of what the Federal Reserve, ECB and China’s PBOC are required to do. The current expansion in the global economy has reached a critical juncture, but Jeremy concludes that the recessionary threat can be calmed down.

Middle East Developments

It must be recognised that there are more downside than upside risks to this central case. While investors are paying considerable attention to the US-China trade talks, there is a range of other issues such as developments in the Middle East which could have considerable implications for oil prices. While many funds do not invest directly in oil, understanding the commodity brings considerable benefits. At a practical level, the price of oil is a key driver of company profits, household disposable incomes, headline inflation and inflation expectations as embedded into bond markets. More fundamentally, oil reflects some of the key drivers in the world economy: the business cycle, especially in emerging markets, political stress, technology and climate change threats.

2020 Predictions

Robert Minter, commodity strategist, puts these issues into context in his article setting out a detailed framework for analysing the energy markets. His conclusions are indeed that, in the short term, a range of political risks could push oil prices towards the higher end of their trading range. However, into 2020 he warns that the next steps in turning the US into a more significant oil exporter should act to dampen prices. Such recommendations feed into the investment process for a range of our equity and fixed-income fund managers in both public and private markets.

In a related article, Curt Starer, Investment Director in US fixed income, examines recent and future changes in the oil price in relation to the credit markets, especially US investment-grade (IG) corporate bonds. He explains how our portfolios remain cautious on energy IG corporate bonds due to their relatively high correlation to macro trends. Fund managers are taking advantage of periods of volatile oil prices and the resultant spread-widening across energy sector bonds to move up in quality and de-risk portfolios.

Viktor Szabo, Investment Director in emerging market debt, asks an important question: “Is the abundance of natural resources, such as oil, a blessing or a curse?”. Fluctuating commodity prices have seriously affected the Russian economy in the last two decades. He concludes that while sanctions have forced the adoption of more prudent macro policies, the lack of structural reforms in general, and support for the private sector in particular, still hinder investor sentiment. Portfolios are underweight Russian hard-currency debt although local-currency bonds still have some attractions.

Download this article

as a pdf

Age of uncertainty –

healthcare investments

Chapter 1

Frances Hudson, Global Thematic Strategist

Long-term developments in demographics and health, rising expenditure in this area are important issues driving trend rates of economic growth. These factors have high-level implications for strategic asset allocation, as well as creating a complex investment environment where active investment decisions are favoured.

Demographic Imperatives

Strategic Asset Allocation

Major economic, social and technological changes need to be considered when making investment decisions, especially when determining strategic asset allocation (SAA). This article looks at some of the consequences of increased numbers of older, less healthy people for long-term market returns. We also consider the implications of current and alternative approaches to healthcare provision, and how changes could improve sustainability. We conclude with how investors are able to incorporate thinking about healthcare in their portfolios.

Rethinking Pensions

Demographic developments connected with ageing pose major challenges in areas such as pensions, health and social care. For many people, retirement marks the beginning or the acceleration of declining physical robustness and mental acuity, which eventually creates the need for increased spending on both health and social care. Rethinking pensions, informed by actuarial projections, has been a long-standing focus of the investment industry. Projections of economic growth, inflation and discount rates translate into required savings and retirement ages, both of which need to rise to avert pension shortfalls. Increasing both could also improve health and reduce the spending that is required on health and social care.

Health Spending

This year marks a tipping point where people aged over 65 outnumber the number of those under five years, globally. Ageing, non-working populations put downward pressure on interest rates and upward pressure on health (sickness) spending. The funding required for healthcare could easily exceed the estimated shortfall for pensions of $400 trillion by 2050. However attention to healthcare has lagged, perhaps because the problem is inherently messy and mutable.

Healthcare is paid for by a mix of public, private and insurance contributions, which vary widely from country to country. Healthcare spans public, private and tertiary sectors, plus a range of industries and services from the traditional to the cutting edge. As a topic, it is harder to define and contain than pensions or social care, and human interactions feed into the changing landscape.

Living up to potential

Leaving aside flamboyant aspirations of living for a thousand years and the misconception that life expectancy for babies born in recent years is hovering around 150 years, average life expectancy has been extended. With the exception of those living in places of conflict or where the climate poses difficulties, more people are realising their potential lifespan because of a decrease in child mortality in both developed and developing economies. For those born in 2016, the average lifespan is 72 years. Some nations have a lifespan of more than 80, while Russia and populous India hover around 70. However sustainability is not just about the number of years a person lives, but the quality of those years; healthy life expectancy is around nine years shorter than full life expectancy (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: Living the healthier dream

Sustainability is not just about the number of years a person lives, but the quality of those years; healthy life expectancy is around nine years shorter than full life expectancy (see Chart 1).

The average expenditure on health has grown in both developed and developing countries. In developed countries it has risen as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) from 7.8% in 2000 to 10.3% in 2016. For developing countries, the figures are 4.8% to 5.8%, respectively.

Chart 2: Who spends wins?

The trend is sharply upward in both cases and underlines sustainability concerns as potential economic growth is subdued (see Chart 2).

Source: OECD, Aberdeen Standard Investments (as of June 2019)

Source: OECD, Aberdeen Standard Investments (as of June 2019)

While US per capita spend is significantly higher than elsewhere, it is relatively ineffective in terms of increasing lifespans. Part of the explanation lies in how and where money is spent and epitomises the effect of unequal societies. Medicare and Medicaid, federal health insurance programs for seniors, permanently disabled and low income people, accounted for 37% of US national healthcare spending in 2017, equating to $1.3 trillion. The figure has risen 66% in a decade and is projected to increase at a faster pace over the next decade. Private insurance spending is rising even more rapidly without improving outcomes.

Sustainable Heathcare – ‘If I were going there, I wouldn’t start from here’

Aspects of an affordable and sustainable healthcare system may seem obvious: where possible focus on health rather than sickness, prevention rather than (expensive) treatments, immunisation for communicable diseases, and individual responsibility for health outcomes. In principle, it is hard to argue against primary care or treatment in the community rather than hospitalisation. Unfortunately nowhere is starting with a clean sheet.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

In 2016, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries spent the equivalent of just 0.3% of GDP on prevention. Those who pay the piper, call the tune; in many cases, sources of funding determine priorities. In emerging economies, building the infrastructure and widening coverage is high on the agenda. One risk is that rather than leapfrogging established healthcare models, and opting for prevention and sustainability, they adopt practices and protocols that are no longer fit for purpose.

Access to healthcare

Access to healthcare tends to be better for higher income cohorts. Even where provision is nominally universal, the immediate demands of treating the sick can overwhelm longer-term considerations and resource commitments to preventive healthcare. This argues for separate funding for preventive healthcare and tackling morbidity. It is also not clear who leads the charge. Corporate motives in the healthcare sector are notoriously conflicted, political time horizons are too short, the benefits from spending on education and prevention are hard to identify, and money that is set aside is a soft target for cash-strapped decision makers.

Changing Landscape

Morbidity progress

Tom Lehrer referred to ‘specialism in the diseases of the rich’ as a doctor’s route to riches and early retirement. Since there is an established link between affluence and longevity, this makes sense. Looking at the causes of morbidity and premature mortality is helpful. Progress on tackling morbidity in affluent societies reflects where money is being spent but there are gaps.

Obesity growth

Obesity has tripled in the last four decades in developed markets, while similar trends are developing in more affluent emerging markets. The associated growth in metabolic syndrome has increased the risk of type-two diabetes, heart attacks and strokes. Another tripling would render healthcare systems unsustainable in most countries. Lifestyle diseases associated with obesity or an overindulgence in addictive substances (tobacco, alcohol, caffeine, and drugs including cannabis and opioids) are commonplace and carry serious cost implications. These are conditions that should be targeted through prevention and education.Other diseases

Along with heart disease and strokes, dementia is a major cause of death in high-income countries and it is attracting more resources aimed at finding remedies. Progress is patchy, though, with recent breakthroughs in tackling some cancers while others are still intractable.

Future Health

Machine learning

There are sources of optimism in healthcare as well as long-standing tensions, such as the question of drug pricing and the premium patented drugs pipeline versus generics. The application of new technologies could make a substantial difference. The buzzwords may be familiar – big data, artificial intelligence (AI) and robots – but in healthcare they are enablers rather than ends in themselves. Examples include robotic elements to surgery, 3D printing of skin for treating burns, joints for hip and knee replacements, and the use of algorithms for triage and updates of surgical checklists. For drug companies, big data and AI can speed up drug discovery. Unsupervised machine learning, utilising clustering for simulations and testing, increases productivity and reduces costs.

With new tools and processing power, personal data can be used and shared more effectively (and suitably safeguarded and anonymised where appropriate). This offers the potential for substantial savings, particularly in primary care where the fragmentation of data has been a problem. For individuals, a blockchain-enabled personal health record would facilitate a whole life approach to healthcare, which would avoid data loss.

DNA sequencing

A lot of progress has been made in personalised medicine, thanks to DNA sequencing. Gene sequencing is the basis for genomics or gene editing via CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats). Synthetic biology marries biotechnology with engineering to digitise DNA, meaning that individual cells can be reprogrammed. These technologies are on the cusp of reducing the incidence of certain diseases and conditions, which should change their outcomes. The analysis of the trillions of microbiomes – the bacteria or phages that inhabit the gut – shows how individuals respond to stimuli, including food.

For example, twins can have different body shapes and outcomes despite the same diet and exercise, because gut bacteria determines how carbohydrates are metabolised. Non-exhaustive potential microbiome applications include an alternative to antibiotics, dealing with obesity (and related depression), autism, autoimmune diseases, food poisoning (salmonella), Alzheimer’s, type one diabetes, and drug treatment responses. Microbiomes fit the prevention profile and it’s not just about ingesting pro-biotics (bio yoghurt). Diverse nutrients and exercise can alter microbia.

In neurology, meanwhile, using AI to re-establish neural pathways following strokes or brain damage appears promising. Reversing ageing in cells is the ultimate prize for which to strive. If that can be achieved, maybe the answer to who wants to live forever could be ‘yes’.

Life extenders

Paradoxically, some of the ways to extend life (antibiotics, immunisation, better hygiene and anti-bacterial measures) are also linked to a four-fold increase in chronic illness. Negative scenarios include rising antimicrobial resistance where antibiotics and standard treatments become ineffective, and where infections persist and spread. This poses the risk of pandemics. At a more basic level, bureaucracy and misguided management, mishandling of personal data, legal challenges and ethical questions all need to be tackled in the quest for workable and sustainable healthcare.

Investing in Health

Strategic Asset Allocation

The mental and physical health of a population is a key driver of the labour force and long-term economic growth. Demographic headwinds and rising pressures on health versus non-health budgets suggest that future market returns will be lower than in the past. In addition to the implications of health for the Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA) investment process to determine long term returns, where and how should investors gain exposure to health as an investment theme? As with most health-related questions, the answer is not straightforward. Healthcare was traditionally seen as a defensive sector, close to a bond proxy. Established blue chip pharmaceutical companies offered generous dividends, underpinned by predictable cash flows for the duration of patents. The sector is very different today as consolidation and spinoffs abound, as companies rearrange their assets, and as service providers and insurance elements co-exist with drug and device manufacturers and innovative therapies.

Chart 3: Healthcare performance is anything but generic

The regulatory debate is shifting, especially in the USA , where healthcare is again a major topic in the run up to the 2010 presidential elections. In a world of low growth, large blocks of capital chase promising new technologies. Biotechnology and life sciences sit at the disruptive end of the spectrum. They are as likely to be found in venture capital and private equity space as subsidiaries of established companies. As a result, performance at the sub-sector and industry level varies widely (see Chart 3).Source: Bloomberg, Aberdeen Standard Investments (as of June 2019)

The division between winners and losers is marked and failure rates are high, which argues for an active and diversified approach to investing.

In general, access to healthcare is better for higher income cohorts.

Gathering Storm Clouds

Chapter 2

Jeremy Lawson, Chief Economist and Head of ASI Research Institute

We forecast sluggish global growth into 2020, with business confidence and investment adversely affected by political and trade tensions. However, policy easing should calm the recessionary threat.

Failure to ignite

The current expansion in the global economy has reached a critical juncture. Although growth picked up worldwide in the first quarter, driven by improvements in the US, China and the Eurozone, elsewhere most economies have been struggling. GDP contracted in Argentina, Brazil, Russia and South Africa, while it was very weak in countries ranging from commodity importers like India, to commod ity exporters such as Australia and Canada, and to the ‘super trading’ economies like Korea and Taiwan.

Manufacturing, trade and investment indicators have been weighed down by uncertainty over the geopolitical outlook.

Chart 1: Distortion of tields

Certain sectors have been particularly subdued of late. Manufacturing, trade and investment indicators have been weighed down by uncertainty over the geopolitical outlook. Indeed, global trade volumes fell in the six months to March, and the global manufacturing PMI has declined to its lowest level since 2012 (see Chart 1).

As a consequence, our ‘Nowcasts’ imply that the global economy’s underlying growth rate in Q1 was weaker than the headlines suggest and that momentum has weakened further into Q2.

Politics affects business

The reluctance of firms to commit to expensive capital projects with distant payoffs is easy to understand. Take the UK - while Brexit may have been delayed until the end of October, the prospect of political compromise appears more distant than ever. Prime Minister May has been forced to resign, after her three failed attempts to broker a compromise between the warring factions. Meanwhile, the big winners from the recent European elections were the Brexit Party and the Liberal Democrats, the former pushing for a ‘no-deal’ Brexit and the latter to remain within the EU. This left the two main parties floundering.

This push against the established parties was also evident in the broader EU election results. Far-right groups made gains across the continent but so did the Greens, as well as some of the newer centrist parties. The upshot is that the new European parliament will be among the most fractured in history. Populists may not be in a position to force the EU apart. Nevertheless, mainstream politicians are likely to heed the message that voters are wary of ceding any more power to Brussels - even if that limits structural reforms and leaves the bloc more vulnerable to future crises.

Perhaps the most ominous result came from Italy where the League party bested its coalition partner, the Five Start Movement, and is now spoiling for a fight with Brussels over the country’s next budget. The European Commission, having issued a warning of intent to place Italy in an Excessive deficit procedure, appears only too willing to call its bluff. It is no surprise that Italian government bond spreads have been wide for much of this year, keeping financial conditions tight, before narrowing as ECB quantitative easing hopes grow.

Trade tensions mount

Most important of all, the trade war between the US and China has reignited. This followed the failure of senior negotiators to close the gap between US demands for significant and legally binding Chinese action (to curtail unfair trade, investment and intellectual property practices) and China’s requirement for a more balanced and respectful agreement. In response, the US has raised the tariff rate from 10% to 25% on close to $200bn of Chinese goods imports and threatened to impose tariffs on all imports if China does not make significant concessions over the coming weeks.

Chinese technology companies

The US has also taken further actions to limit the ability of Huawei and other Chinese technology companies to participate in the development and roll-out of 5G telecommunications networks, and in trade more broadly with US companies. Worsening rhetoric on both sides and threats to supply chains – for example through action to curtail trade in rare minerals – is further dampening business confidence. The recent G20 trade truce does not remove these structural issues.

Mexico tariffs

On top of that, the US government temporarily opened up a new front by threatening to impose tariffs on Mexico if it did not take “sufficient” steps to restrict the flow of refugees and illegal immigrants across their shared border. The government quickly withdrew the threat when Mexico responded with remedial actions and under intense lobbying pressure. However, the episode has added to the uncertainty facing the auto industry, which is already operating under the shadow of the Section 232 investigation into unfair foreign export practices.

Taking all those headwinds into account, our latest forecasts imply that global growth is likely to flat line between 2019 and 2020 at a rate below the post-crisis average, rather than pick up as we previously expected.

Déja vu for central banks

Central banks have reacted to the latest slowdown, increased political uncertainty, stubbornly low inflation and strong bond market signals that policy settings are currently too tight by conceding the need for a more accommodative policy stance. Most notably, US Federal Reserve (Fed) rhetoric has evolved from implying that their tightening cycle is more or less done to stating a willingness to act should the trade war escalate and the economy or markets slump. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has already loosened policy significantly over the past year, yet appears ready to take further steps to support the economy.

Other major central banks also have room for manoeuvre. This repeats the pattern seen multiple times during the post-crisis expansion, demonstrating that self-sustaining growth remains as elusive as ever.

Central banks should not be left alone to face these challenges. With interest rates and potential growth so low, and most countries facing acute infrastructure shortages exacerbated by climate change pressures, there has never been a better time to loosen fiscal policy and ramp up public investment. Unfortunately, just as fractured politics are increasing business uncertainty and raising the barrier to investment, they also make it more difficult to coordinate a large fiscal easing. So, in the end, central banks will once again need to take up the slack.

Cutting interest rates

We expect the Fed to kick things off by cutting interest rates twice in the second half of the year, with the PBOC also taking further steps to cut policy rates and boost credit demand via easier bank regulation. Australia and India both recently cut rates, with more to follow in the second half of the year. We anticipate rate cuts in many of the other major economies, including Brazil, Canada and Russia. Even more critically, Mario Draghi provided a strong signal that rate cuts and the resuscitation of quantitative easing are back on the table in the Eurozone. The Bank of Japan is also looking for ways to provide additional stimulus.

Setting at a lower altitude

If the major central banks do as we expect and governments avoid further policy mistakes, this ought to be enough to stabilise global economic and corporate earnings growth, albeit at rates lower than the average since the financial crisis. We acknowledge the widespread perception that two Fed rate cuts would not be enough to prevent a more severe downturn, because markets appear to be discounting even more aggressive easing.

Chart 2: Sluggish periods for trade and manufacturing

We do not think such a view accounts for the way the yields on US and other defensive assets are being distorted by lower inflation-risk premia, sizeable central bank balance sheets and other, regulatory, sources of price-insensitive demand for bonds (see Chart 2).

This judgement is reflected in our new forecasts that show global growth holding just above 3% this year and next. However, that still represents a significant downward revision from our previous forecasts. Against a backdrop of low inflation and only moderate US economic and financial imbalances, the shape of the interest rate yield curve is more an indicator of slow growth ahead and the need for policy easing than an imminent recession.

Among the major economies, we expect the greatest initial deceleration in growth to take place in the US. This reflects its epicentre in the growing number of trade disputes, as well as the impact of the fading effects of 2018’s tax cuts and increased government spending (see Table 1). We also anticipate that Chinese growth will be on a moderating trend as additional stimulus is unlikely to be large or efficacious enough to counteract the trade policy headwinds.

Table 1: GDP Growth and CPI inflation

Among the major economies, we expect the greatest initial deceleration in growth to take place in the US. This reflects its epicentre in the growing number of trade disputes, as well as the impact of the fading effects of 2018’s tax cuts and increased government spending (see Table 1).

Source: Bloomberg, Aberdeen Standard Investments (as of Q2 2019)

Source: Bloomberg, Aberdeen Standard Investments (as of Q2 2019)

We also anticipate that Chinese growth will be on a moderating trend as additional stimulus is unlikely to be large or efficacious enough to counteract the trade policy headwinds.

In the Eurozone and Japan, our forecasts have also come down, reflecting the influence of the external environment. However, we expect their modest expansions to continue while domestic monetary and financial conditions remain highly accommodative. That also holds true for the UK, conditional on a no-deal Brexit being avoided – otherwise all bets are off.

Major emerging markets

Meanwhile, in the major emerging markets other than China, there is actually scope for growth to pick up over the next few quarters. That is partly a function of the easing in domestic and foreign monetary policy we are factoring in, but also an arithmetical effect from an unduly weak start to the year.

As for inflation, we have long believed that the impact of falling unemployment on wages and consumer prices would be limited. This reflects both how well-anchored expectations are and the various structural forces constraining firms’ ability to pass on labour cost increases to final core prices.

Our more subdued growth outlook only serves to reinforce that picture, although tariff increases will temporarily push up prices in affected economies.

Forecasting uncertainty is high

Economic projections

Politics are an overarching threat to our economic projections. Trade talks and strategic rivalry between the US and China are likely to be enduring features of the economic and investment landscape, although their manifestations will ebb and flow. The recent agreement between Presidents Trump and Xi at the G20 summit to re-start trade negotiations is only be the first step on a long and complex path.

Unfortunately, as the global expansion is more than a decade old, and a range of debt imbalances exist in many countries, the risks to our outlook are tilted to the downside. There are also question marks about further political disruptions, and about the efficacy of the policy easing we have factored in, and indeed whether it comes quickly enough, in relation to worryingly low levels of business confidence.

Upside Risk

Of course, upside risks should not be ignored. A soft resolution to Brexit, another rapprochement between Italy and the EU and a tactical retreat over trade policy threats amid sustained market and political pressure, could all make near-term uncertainty less acute. Combined with proactive monetary policy easing and healthy labour market trends lifting consumer demand, the preconditions for a solid inventory-led upswing would come into view. A complex interaction of political, policy and economic waymarks will determine which of these scenarios plays out.

Manufacturing, trade and investment indicators have been weighed down by uncertainty over the geopolitical outlook.

What’s driving oil prices and

where are they heading?

Chapter 3

Robert Minter, Investment Strategist Commodities, Global Strategy

Our forecasts suggest short-term upside and longer-term downside to the oil price, reflecting an objective assessment of a wide array of demand, supply and risk indicators.

Forecasting oil prices? Not so easy!

Chart 1: Energy intensity of various economies over time

It is generally assumed that global economic activity drives oil demand and hence prices. In fact, looking back over the past 35 years, such a relationship is weak and does not fully explain oil price movements. One reason is that the energy intensity of the global economy fell by one-third between 1990 and 2015 (see Chart 1).

Politics are an overarching threat to our economic projections.

Chart 1: Energy intensity of various economies over time

Data disconnect

Non-OPEC producers

Why is this relationship between economic growth and oil prices changing? One reason is technology, especially shale production. There has been an increase in the market share of non-OPEC (The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) producers, particularly in the US.

As US production has risen, US import demand has fallen and US exports have climbed from zero to over three million barrels per day (about 3% of global supply). US supply is determined not by OPEC meetings but by each corporate producer, based on internal profit dynamics. Moreover, US shale oil producers can add or remove supply much more quickly than most global sources.

Commodity markets

A second reason is the financialisation of commodity markets. In recent years, financial market participants have become important players in this sector. They have been able to drive the price of oil above and below fundamentally justified ranges for periods of time.

For example, commodity trading advisors typically rely on momentum trading. Other financial market players are driven by ‘roll yield’ – the profit or loss incurred by closing out a futures position as it nears expiration, and opening a new futures position with an expiry date further away. For other money managers, oil’s unique qualities make it an attractive diversifier, helping offset geopolitical risks elsewhere in a portfolio.

Oil market pricing

Another contributor to the inefficiencies in oil market pricing is the poor quality and timing of data. A UBS report in 2014 showed that the average miss on the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) oil market balance was one million barrels per day. This magnitude of error explains 90% of the variability in the market and renders the IEA’s current estimates virtually useless. Their accuracy is only helpful after revisions are complete two years later!

Building robust forecast

Given the difficulties in making sense of oil market data, how can we build useful oil market forecasts?

In our own analysis, we overcome the data issues by: seeking objective data from multiple sources; seeking contrarian advice; and using a range of market data to negate those data signals for which confidence is low.Energy scorecard

Using these principles, we can create a proprietary energy scorecard. This includes analysis of over 50 commodity research sources from a mixture of industry bodies and investment bank specialists. Such breadth of research means we can identify factors that have historically shown a close relationship with global oil prices, and which can therefore be useful forward indicators.

We group indicators into six major categories: valuations, demand, supply, technical analysis signals, externalities and risk, each of which has a score indicating a positive or negative price outlook.

Valuation

Valuation indicators include consumer price inflation, the world output gap and the US dollar trade-weighted index. Additionally, we take account of the ‘new project cost-curve’ – the price which, if exceeded, would incentivise a big increase in production. Currently, valuations are above historical ranges but not in previously established danger zones. Oil prices are below but approaching levels that would trigger new production.

Demand

Demand indicators include guidance from our ASI Research Institute specialists. We also use economic surprises indices from the US, China and EMEA, which often represent data not already assimilated into the oil price. These and other demand indicators imply solid oil demand growth of 1.4% in 2019. However, demand is typically lower in the first half of the year than the second half, so we are heading into a seasonally strong period.

Supply

Supply indicators are positive for higher oil prices. Supply is tightening because of falling production in Venezuela and sanctions against Iran. Added to this are pipeline capacity constraints in the US, OPEC production cuts and low inventories in Europe arising from the Russia-Europe pipeline outage.

Technical analysis signals

Price signals are also positive. As an example of one measure we follow, the Saudi Aramco premium or discount to the official selling price is currently at its highest level since 2014.

Externalities and risk

Externalities include supply disruptions, geopolitical tensions, the effects of sanctions and cartel activity. Currently, these also point to upward pressure on oil prices over the summer.

Risk – lastly, there is a range of political risks that could materially affect supply or demand. Most of these are scoring negatively at present. For instance, if the US-China trade dispute escalates, our expectations for oil demand and pricing could prove to be too high.

Our current oil market view

On a three-month time horizon, we remain positive on the oil sector outlook. Fundamentals justify a price range of US$60-70 per barrel(pb) for Brent crude. We are entering a period of strong seasonal demand, while elevated geopolitical tensions and limited spare capacity will constrain supply.

Our findings suggest the oil market will be undersupplied until October, when it will shift into oversupply going into 2020, as more US supply steadily comes on stream allowing higher exports. On that basis, we expect oil prices to be in the lower part of their trading range in the coming year.

Politics are an overarching threat to our economic projections.

Selective buying

in energy bonds

Chapter 4

Curt Starter, Investment Director (US Fixed Income)

We are cautiously navigating the energy sector through this period of trade and regulatory uncertainties, by favouring differentiated mid-stream and higher quality companies.

Tariffs = wider bond spreads

Heightened volatility in US investment grade (IG) credit has led to a disconnect in current bond prices relative to underlying corporate fundamentals within select sectors. Stalling US-China trade negotiations and potential tariffs on Mexico, among other foreign policy and regulatory actions, have lowered business confidence and hence global economic growth expectations. These headwinds have been only partially offset by dovish commentary from the Federal Reserve. Such uncertainty has particularly weighed on companies in the industrial sector that are most sensitive to the macro-economic environment, especially within the energy space. This has driven corporate bond spreads for IG energy companies ~30bp wider to ~160bp since early May, retracing about 85% of the tightening seen this year (see Chart 1). In comparison, spreads for all industrials only widened by about 19bp to 133bp.

Energy debt remains strongly linked to global macroeconomic concerns.

Tariffs = wider bond spreads

Heightened volatility in US investment grade (IG) credit has led to a disconnect in current energy bond prices relative to underlying corporate fundamentals within select sectors. Stalling US-China trade negotiations and potential tariffs on Mexico, among other foreign policy and regulatory actions, have lowered business confidence and hence global economic growth expectations. These headwinds have been only partially offset by dovish commentary from the Federal Reserve.

Chart 1: Growing global concerns widen options spreads

Such uncertainty has particularly weighed on companies in the industrial sector that are most sensitive to the macro-economic environment, especially within the energy space. This has driven corporate bond spreads for IG energy companies ~30bp wider to ~160bp since early May, retracing about 85% of the tightening seen this year (see Chart 1). In comparison, spreads for all industrials only widened by about 19bp to 133bp.

Energy matters

IG investors are struggling with conflicting issues in the energy markets. Current crude oil prices are not reflecting long-term supply and demand fundamentals. Crude supply continues to tighten due to political factors, such as falling production in Venezuela and US sanctions on Iran. In Venezuela, political unrest has reduced activity and investment, resulting in production plummeting from 1.3million barrels per day (mbpd) to 0.8 in the past year. As for Iranian sanctions, waivers granted by the US to eight countries expired in May, cutting demand for Iranian crude towards zero. Iranian production has fallen from 3.8 to 2.3 mbpd since the start of the year.

OPEC members

Furthermore, OPEC members have begun to indicate they will extend production cuts as their June meeting approaches. Non-OECD producers continue to see declining production due to underinvestment, down an estimated 1.5mbpd since the start of the year according to the US Energy Information Administration. Tensions have also risen after attacks on two tankers in the Strait of Hormuz. This brought potential supply disruption into question; about a third of the world’s sea-borne oil passes through this area every day. Higher US shale production has partially offset these pressures, but this source of supply is self-restrained by the focused financial discipline of US producers.

Global population growth

On the demand side of the equation, global population growth and the push to modernize developing countries drives crude oil demand up by 1.3-1.5mbpd per annum. Only in times of global recession or significant financial stress do we see crude oil demand growth fall below 1.0mbpd. Although economic growth looks to be moderate in coming years, and while risks related to trade tensions that were thought to be low under normal circumstances not so long ago have increased between the US and other countries, we are forecasting steady demand-growth.

Our investment strategy

We are taking advantage of periods of volatile oil prices, and the resulting spread widening across energy-sector bonds, to move up the quality scale and de-risk portfolios. Spreads have widened back to mid-2016 levels when the average energy company was leveraged by over 5x and ‘burning’ through cash. Today, energy companies are fundamentally far stronger credits with leverage of 2x-3x on average, with a breakeven oil price of $50 per barrel or better for WTI crude and are generally free cash flow neutral at worst.

Oil processing-pipeline

Midstream (oil processing-pipeline) companies remain a sweet spot in the sector as most of these companies have stable cash flows supported by long-term fee-based arrangements, and have simplified their corporate structures. They have also improved their cost of capital and are now retaining sufficient cash flow to cover a significant portion oftheir capital expenditure. Equity investors are still generally wary of this subsector, while debt investors appear lukewarm, providing an attractive opportunity for longer term investors.

Energy debt

Despite the general improvement of underlying credit fundamentals among energy companies, there are still reasons to be cautious. Energy debt remains strongly linked to global macroeconomic concerns. The sector is large, so there are plenty of securities for investors to short in times of real or perceived economic weakness.

Energy service companies, in particular, have not seen the same fundamental improvement as their upstream oil & gas counterparts. Excess capacity has limited pricing power and hindered profit margin recovery. Only services companies in niche markets or commanding market influence are faring well.

Summary

As global economic growth has come into question, prompted by the state of US-China trade negotiations, so we have seen spikes and dips in oil prices. We remain cautious on energy IG corporate bonds due to the relatively high correlation of such to macroeconomic trends. We are using periods of price dislocation to move into solid midstream producers or into higher quality energy names. While energy service companies are the highest risk opportunity, there are still pockets of value.

Energy debt remains strongly linked to global macroeconomic concerns.

Russia – is the abundance of

natural resources a blessing or a curse?

Chapter 5

Victor Szabo, Investment Director, Emerging Market Debt

Fluctuating commodity prices have seriously affected the Russian economy in the last two decades. Sanctions have forced the adoption of more prudent macro policies but the lack of structural reforms still hinder investor sentiment.

A time of change

For many years the abundance of natural resources has been a blessing for Russia. It helped a recovery from the miserable 1990s and the economic collapse precipitated by the disintegration of the Soviet Union, culminating in an exceptionally rare default on domestic sovereign debt. In the first 8 years of the new millennium, steadily rising commodity prices fuelled a seemingly golden age for Russia. Economic growth averaged 7.5% a year.

Reliance on the energy sector

The downside from huge windfall revenues was increased reliance on the energy sector rather than a more diversified economy. Large sums of money found their way abroad, legally or illegally, for example in purchases of luxury property or famous sports clubs. As a result, the economy has lacked much-need investment in the non-energy private sector.

New found wealth has enabled a social contract. People seemed to accept the establishment of a kleptocratic Kremlin regime, with extremely wealthy oligarchs, powerful security structures and limited political freedom in exchange for rising incomes and generous social policies.

Even in those years of rapid growth and huge fiscal and current account surpluses, there were warnings about the risks of overdependence on oil and gas. In early 2008, Russia launched several reserve funds. These were supposed to accumulate hard currency when oil prices were high and plug budget holes when commodity revenues fell, helping smooth the economy. However, Russia soon learned that such war chests were far from sufficient.

Ending with a crash

The crisis of 2008-09 pushed commodities prices into a nosedive, and the Russian economy into deep recession. The blow was further aggravated by persistent capital outflows and a large budget deficit, forcing authorities to tap the newly created reserve funds. It would have been the perfect opportunity to rethink the Russian economic model and work on structural reforms to create a better business environment for the non-energy sector. However, as is typical in highly centralised regimes, initiatives coming from the top failed to attract private participation.

Russia commitment

Despite oil prices reaching $100-120 a barrel in 2011-13, the previous shine never returned. Economic growth struggled to exceed 3%, overburdened by the costs of the crisis, the social contract and general economic inefficiency. The breakeven oil price to balance the budget skyrocketed from $27pb in 2007 to $115 by 2010. Russia had to abandon its commitment to filling up reserve funds, instead being forced to deplete them.

Russia sanctions

Since 2010, Russia has waxed and waned about adopting structural reforms, partly related to internal or external pressures. A series of minor reforms were brought to a halt after street protests in the aftermath of the rigged parliamentary elections of 2011. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 forced some change.

A new social contract offered the restoration of Russia’s superpower status in exchange for foregoing civil liberties and income growth. Indeed, the administration embraced the double blow of lower commodity prices and international sanctions with a set of prudent macro policies. The cost was another recession, currency devaluation and a prolonged period of falling real wages.

The threat of further sanctions created a new policy objective: reducing external vulnerabilities, including the dependence on commodity price movements, while also keeping international oil prices high through cooperation with OPEC.

The government has raised oil industry taxes, hiked VAT, increased the pension age, and introduced new fiscal rules to bolster the wealth funds. As a result, the budget breakeven oil price was pushed below $50 last year. Currency intervention by the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) has also significantly reduced oil price-induced volatility for the ruble.

What is the outlook for Russian debt?

Overseas investors face a difficult situation. While more prudent fiscal and monetary policies have weakened the commodity link, the diversification of the economy away from the energy sector has largely failed to materialize.

Chart 1: Non-fuel impact on Russian budgets

Russia’s centralized and oligarchic economic structure discourages private investment, while the lack of rule of law significantly raises the required rate of return on investments. All in all, Russia is caught between oil prices high enough to avoid recession, but not low enough to force the administration into much needed structural reforms (chart 1).

Since 2010, Russia has waxed and waned about adopting structural reforms.

In our EM debt funds we are underweight Russian hard currency debt, as we think the strong fundamentals have adequately been priced in. In addition, we consider that the risk of further US sanctions is not priced in sufficiently by many investors. Similarly, we are underweight the currency, as fiscal rules cap its appreciation potential.

We do see value in local currency bonds though, as we expect the CBR to continue to cut interest rates. Rates were lowered by 0.25% to 7.5% in June, as both growth and inflation came in below the CBR’s forecasts. Its statement was dovish, guiding for further rate cuts, with a neutral level seen as 6-7%. The CBR has warned, however, of its readiness to respond with tighter policy if the government decides to spend some of the reserve funds in a way not viewed by the CBR as increasing the economy’s potential rate of growth.

Since 2010, Russia has waxed and waned about adopting structural reforms.